Les Nourritures Terrestres: Le Ventre de Paris Zola

Do you love reading? Do you love food? If so, this column is for you!

Hey everyone, I am Aurore, a 20 years old French exchange student. In this new column ‘ Les Nourritures terrestres’, I will combine articles about France, wine and champagne and food culture. This article is the first of a series in which I will try to find the most beautiful and handsome examples of literature about food, meals and cuisine. A great way to combine both passions and to generate the appetite to devour that book.

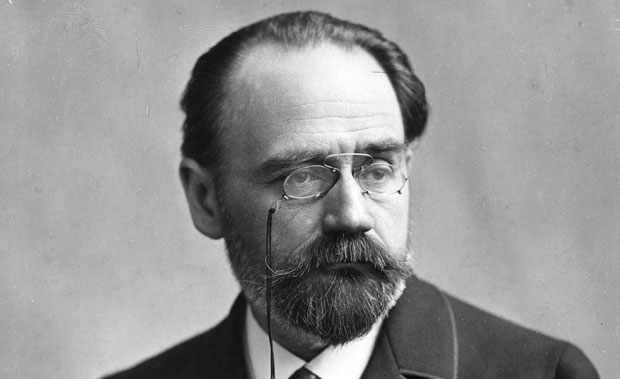

So let ’s start with a wonderful description of the Halles de Paris by Emile Zola in The Belly of Paris.

To whet your appetite, here follows a quick summary of the book. As you may or may not know, E. Zola is a famous 19th century french naturalist writer and journalist. Apart from his novels, Zola is known for its political implication in the Dreyfus Affair. To give to the non-French history specialists a clue of what I am talking about, from 1984 to 1904, the Dreyfus Affair divided France, tore families apart and parted the media. The general Dreyfus was falsely accused of collaboration with Germany because he was a Jew. Zola, in the Aurore newspaper, wrote a famous open letter ‘ J accuse…!’ denouncing government antisemitism and advocating for Dreyfus.

The Paris Belly is part of a larger series named Les Rougon Macquart following a Parisian French family during the Second french Empire. The plot of the novel is mainly around political opinions and implications of the main character and the rise of republicanism under the reign of Louis Napoleon. Florent, a young republican who has just escaped from jail, is going to find a shelter in the Halles. His sudden appearance will disrupt the life of his half-brother Quenu, who owns a major charcuterie in this Parisian market. Interestingly, in the early drafts of Paris Belly, Zola stipulated that:

“L’idée générale est le ventre ;

le ventre de Paris ; les Halles, où la nourriture afflue, s’entasse, pour rayonner sur les quartiers divers ;

– le ventre de l’humanité, et par extension la bourgeoisie dirigeant, ruminant, cuvant en paix ses joies et ses honnêtetés moyennes ;

– enfin le ventre dans l’empire, non pas l’éréthisme fou de Saccard lancé à la chasse des millions, les voluptés cuisantes de l’agio, de la danse formidable des écus ; mais le contentement large et solide de la faim, la bête broyant le foin au râtelier, la bourgeoisie appuyant sourdement l’empire, parce que l’empire lui donne la pâtée matin et soir, la bedaine pleine et heureuse se ballonnant au soleil et roulant jusqu’au charnier de Sedan.”

For those who did not take French 101, I am going to try to give a quick translation of Zola’s vision. Zola stipulated that the whole idea of the novel was the Belly. Florent and Quenu ’s individual stories are ancillary to the whole description of the Halles Market.

The Belly is thus a three dimensional symbol;

- it represents the Halles,with its piles of food and beverages, and it is also the emblem of humanity. Zola uses it to criticize those who prefer their personal subsidence to their political liberty and rights. Finally, it is also the center of the Empire, leaning on and exploiting the fears of the bourgeoisie who rests silently as long as its belly is full.

As you can see the Belly is not only a part of the human body, it is the main thread of the novel.

So, to make your mouth water, here is the most beautiful description of the Halles Market ever written.

“Fruits of all kinds were piled around her in her narrow stall. On the shelves at the back were rows of melons: cantaloupes swarming with wart-like knots, maraîchers whose skin was covered with gray lace-like netting, and culs-de-singe displaying smooth bare bumps. In front was an array of choice fruits, carefully arranged in baskets, and showing like smooth round cheeks seeking to hide themselves, or glimpses of sweet childish faces, half veiled by leaves.

Especially was this the case with the peaches, the blushing peaches of Montreuil, with skin as delicate and clear as that of northern maidens, and the yellow, sunburnt peaches from the south, brown like the damsels of Provence. The apricots, on their beds of moss, gleamed with the hue of amber or with that sunset glow which so warmly colors the necks of brunettes at the nape, just under the little wavy curls which fall below the chignon.

The cherries, arranged one by one, resembled the short lips of smiling Chinese girls; the Montmorencies suggested the dumpy mouths of buxom women; the English ones were longer and graver-looking; the common black ones seemed as though they had been bruised and crushed by kisses; while the white-hearts, with their patches of rose and white, appeared to smile with mingled merriment and vexation.

Then piles of apples and pears, built up with architectural symmetry, often in pyramids, displayed the ruddy glow of budding breasts and the gleaming sheen of shoulders, quite a show of nudity, lurking modestly behind a screen of fern leaves. There were all sorts of varieties — little red ones so tiny that they seemed to be yet in the cradle, shapeless Tambours for baking, Calvilles in light yellow gowns, sanguineous-looking Canadas, blotched châtaignier apples, fair, freckled rennets, and dusky russets. Then came the pears — the blanquettes, the British queens, the beurrés, the messirejeans, and the duchesses — some dumpy, some long and tapering, some with slender necks, and others with thick-set shoulders, their green and yellow bellies picked out at times with a splotch of carmine.

By the side of these the transparent plums resembled tender, chlorotic virgins; the greengages and the Orleans plums paled as with modest innocence, while the mirabelles lay like the golden beads of a rosary forgotten in a box among sticks of vanilla. And the strawberries exhaled a sweet perfume — a perfume of youth — especially those little ones which are gathered in the woods, and which are far more aromatic than the large ones grown in gardens, for these breathe an insipid odor suggestive of the watering pot.

Plump summer fruit for sale.

Raspberries added their fragrance to the pure scent. The currants — red, white, and black — smiled with a knowing air, while the heavy clusters of grapes, laden with intoxication, lay languorously at the edges of their wicker baskets, over the sides of which dangled some of the berries, scorched by the hot caresses of the voluptuous sun.

It was there that La Sarriette lived in an orchard, as it were, in an atmosphere of sweet, intoxicating scents. The cheaper fruits — the cherries, plums, and strawberries — were piled up in front of her in paper-lined baskets, and the juice oozing from their bruised ripeness stained the stall front and steamed, with a strong perfume, in the heat. She would feel quite giddy on those blazing July afternoons when the melons enveloped her with a powerful, vaporous odor of musk; and then with her loosened kerchief, fresh as she was with the springtide of life, she brought sudden temptation to all who saw her. It was she — it was her arms and neck which gave that semblance of amorous vitality to her fruit.

On the stall next to her an old woman, a hideous old drunkard, displayed nothing but wrinkled apples, pears as flabby as herself, and cadaverous apricots of a witch-like sallowness. La Sarriette’s stall, however, spoke of love and passion. The cherries looked like the red kisses of her bright lips; the silky peaches were not more delicate than her neck; to the plums she seemed to have lent the skin from her brow and chin; while some of her own crimson blood coursed through the veins of the currants.

All the scents of the avenue of flowers behind her stall were but insipid beside the aroma of vitality which exhaled from her open baskets and falling kerchief.”

If you enjoyed this excerpt, then you should definitively seek out the whole novel!

Aurore Guglielmi